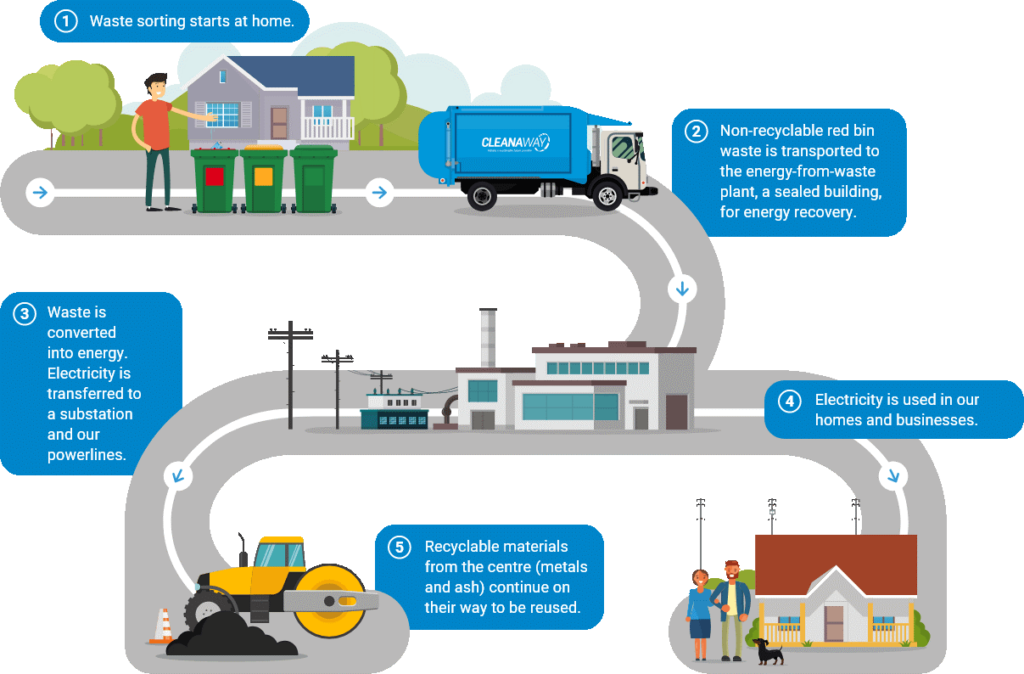

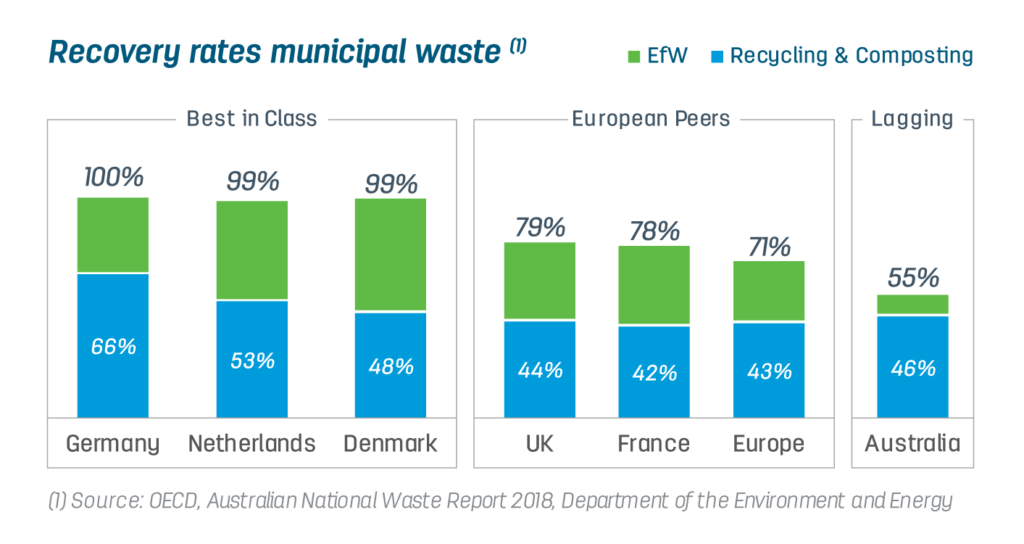

Energy-from-waste is a waste management solution that has been widely and safely used overseas for decades. The technology has been refined over time and is now established as a critical pathway for managing non-recyclable residual waste.

Cleanaway and Macquarie Capital are proposing an energy-from-waste facility in NSW. This facility will turn non-recyclable red bin waste into electricity to power thousands of homes in Western Sydney. Read more about the role of energy-from-waste in waste management here.

Despite its broad use in Europe, energy-from-waste is new to Australians and the technology is poorly understood. Many still associate energy-from-waste with less advanced incinerators of the past, that have not benefitted from the technological advances made since.

For this reason, communities rightly have questions about the technology, its safety and how it works within the context of other waste management options such as recycling. This article aims to raise some of these concerns and provide factual, research-backed evidence to explain the misconceptions in the context of the WSERRC proposal.

Technology

Concern: Incinerators are outdated and ‘energy-from-waste’ is just an incinerator in disguise

Fact: A significant misconception is that energy-from-waste facilities are the same as the commercial incinerators of past.

Whilst energy-from-waste also combusts waste, there are two key differences between a modern facility and the facilities of the past.

Firstly, the facilities are highly engineered to minimise air pollution and protect human health. The facilities are designed to ensure complete combustion of waste occurs, reducing pollutant gases forming and the ash remaining at the end of combustion.

Modern facilities are now also equipped with extensive and efficient Flue Gas Treatment (FGT) systems. These FGT systems have multiple steps that clean the gases, making sure that emissions are at safe levels before they leave the facility.

Secondly the facilities have the ability to recover energy from items destined to be wasted in landfill. Energy-from-waste plants use the heat from the process to turn water into steam, driving a turbine which generates electricity to power homes and businesses.

Concern: Energy-from-waste is being phased out overseas due to concerns with air quality

Fact: Energy-from-waste, as an industry, is not being phased out. What we see occurring is:

a) the closure of older facilities with outdated technology

b) increased support for recycling, reuse and reduction initiatives

Some operators have made the decision to invest in upgrading their facilities to ensure that they are adhering to updated emissions standards and utilising best practice operating techniques and technologies.

Globally, new energy-from-waste facilities are still being built.

Emissions and Health

Concern: Studies show that living near an energy-from-waste facility can be harmful to health

Fact: The most recent studies by reputable independent researchers show that modern plants do not cause identifiable changes in health effects surrounding facilities. These researchers have also put up a series of frequently asked questions and answers about these studies which you can access here.

Studies for older plants do show adverse impact from facilities built without pollution control technologies. That is why the plants like the Waverley Woollahra Incinerator was closed down by the NSW EPA in the 1990s. That is also why the European Union started doing systematic reviews of the engineering of such plants to work out what was best practice and how such plants should be safely designed. This has resulted in many facilities being upgraded to incorporate these modern standards.

Concern: The incineration process emits a large amount of harmful particulate matter

Fact: We are always exposed to small particles from burning/combustion from everyday sources such as cars, trucks, buses, trains, planes, smoking, woodfires in our homes, candles, bushfires, power stations and more. The goal for managing air pollution is to keep the levels as low as possible and for new facilities to not make any significant, or measurable changes to ambient air quality.

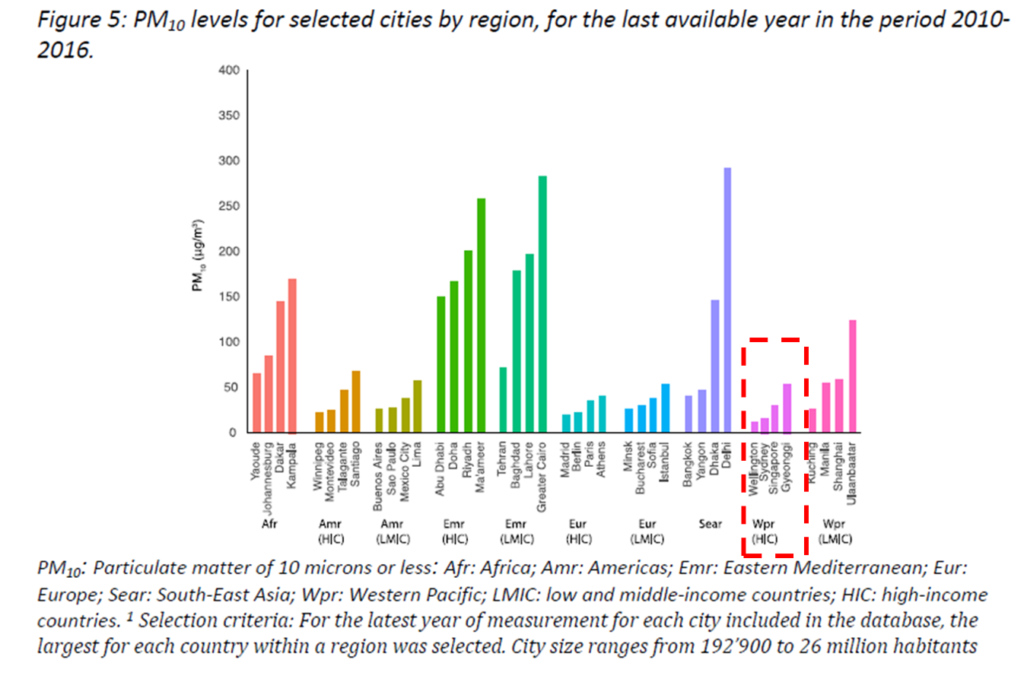

Studies on large groups of people in cities that are used by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) or the World Health Organisation (WHO) give us a basis for understanding what level of effect is small enough to make no measurable difference to ambient air levels.

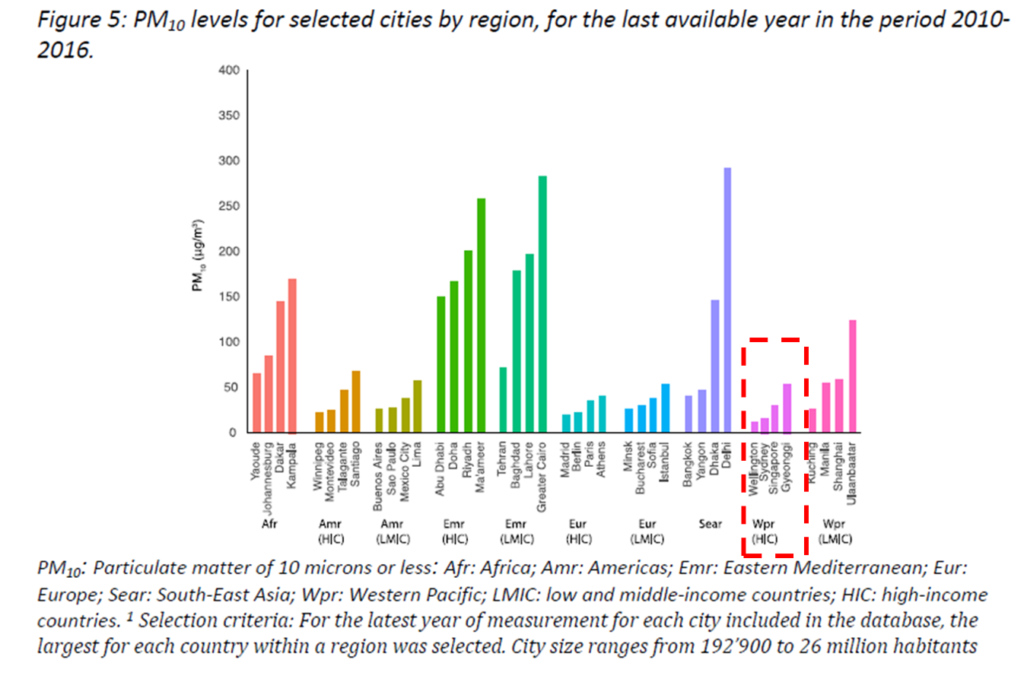

WHO published a summary of air quality for cities across the world where particulate matter (PM10) levels were studied and compared. Only Wellington in New Zealand had a lower average level of PM10 compared to Sydney, which is mainly due to Wellington’s position on a windy peninsula. The whole report can be accessed here.

The mechanisms for how particles cause harm in the body has been studied extensively. Much of the harm comes from the body’s immune response (inflammation) caused by prolonged exposure to high levels of particles. This is why the WHO recommended criteria for annual average fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is 10 µg/m3. The NSW EPA has a criterion of 8µg/m3, one of the most stringent in the world.

In a modern plant, the generation of particles is minimised in the first place by good furnace design, and the vast majority of the particles generated are captured by the flue gas treatment system. Only very low levels of these particles are emitted via a stack so as to ensure they are well dispersed high up into the air. This reduces any potential impact that may arise at ground level where people may be present.

Concern: Emissions from incinerators contaminate drinking water

Fact: The potential for particles to fall into the water supply such as Sydney’s Prospect Reservoir is something that will be assessed in detail in the human health risk assessment. Given that very small amounts of particles will be released from this plant, it is not expected that changes in concentrations in the reservoir would be even measurable, but to ensure thoroughness, this will be checked in the assessment process.

All drinking water contains low levels of most metals like arsenic, cadmium and nickel. Water authorities such as Sydney Water in NSW must supply water to our homes that complies with the drinking water guidelines.

Given the low water solubility of chemicals like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or POPs, and the fact that Sydney Water must always treat water from Prospect Reservoir by filtering it through very fine filters before sending it to our homes, it is unlikely that particles containing these chemicals from an energy-from-waste facility or from any other combustion source will be present in our drinking water.

Regulatory

Concern: NSW’s regulatory controls are outdated

Fact: The NSW energy-from-waste policy enforces the use of world’s best practice technology and emission controls. The policy explicitly states that:

“To ensure emissions are below levels that may pose a risk of harm to the community, facilities proposing to recover energy from waste will need to meet current international best practice techniques, particularly with respect to:

• process design and control

• emission control equipment design and control

• emission monitoring with real-time feedback to the controls of the process”

This requirement ensures that, regardless of the NSW limits, that any energy recovery facility will perform to international top standards. The European IED standards are the most stringent in the world. Given continuous improvements in emissions performance in modern energy-from-waste plants, the EU has recently passed the BREF (Best available technique REFerence document) limits which are significantly lower than the existing IED limits.

Concern: Energy-from-waste facilities should not be located in urban areas

Fact: Internationally, energy-from-waste facilities are commonly located in urban areas. For example, there are multiple energy-from-waste facilities near the heart of Paris located in residential areas. This is because modern energy-from-waste facilities are safe.

For an energy-from-waste facility to be considered for approval in NSW, the submission must first prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Within this EIS is the requirement to conduct a Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA). This HHRA considers the risk of harm to the community that these potential pollutants may cause and must include calculations of how much of the emissions people will be exposed to at the worst-case location. This is the spot where the concentrations in air impacted by the facility are the highest and is usually very close to the facility.

To assess the highest possible exposure that may occur, it is assumed a person lives at that worst-case impacted location for 24 hours per day, 365 days per year for 35 years from birth. The government requires that the calculations for the worst-case location are within guidelines. If not, the location is simply not approved for use.

The assessment will also include calculations at the actual closest houses, workplace, schools and childcare centres nearby and must specifically demonstrated compliance to standards.

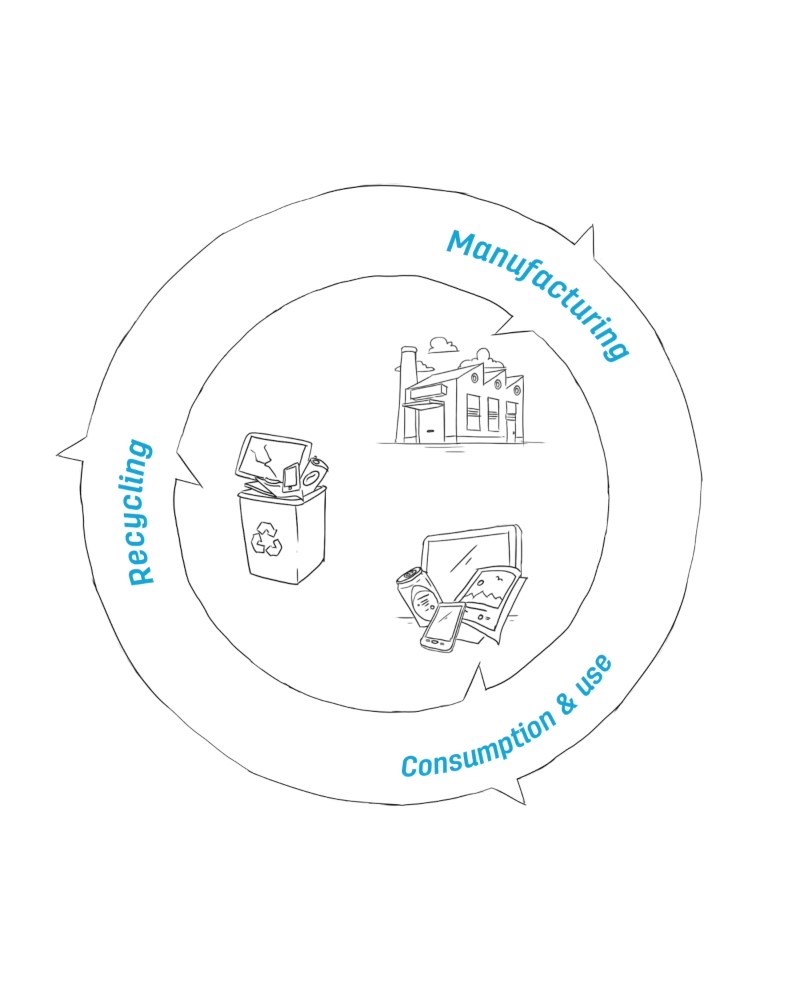

Recycling and the circular economy

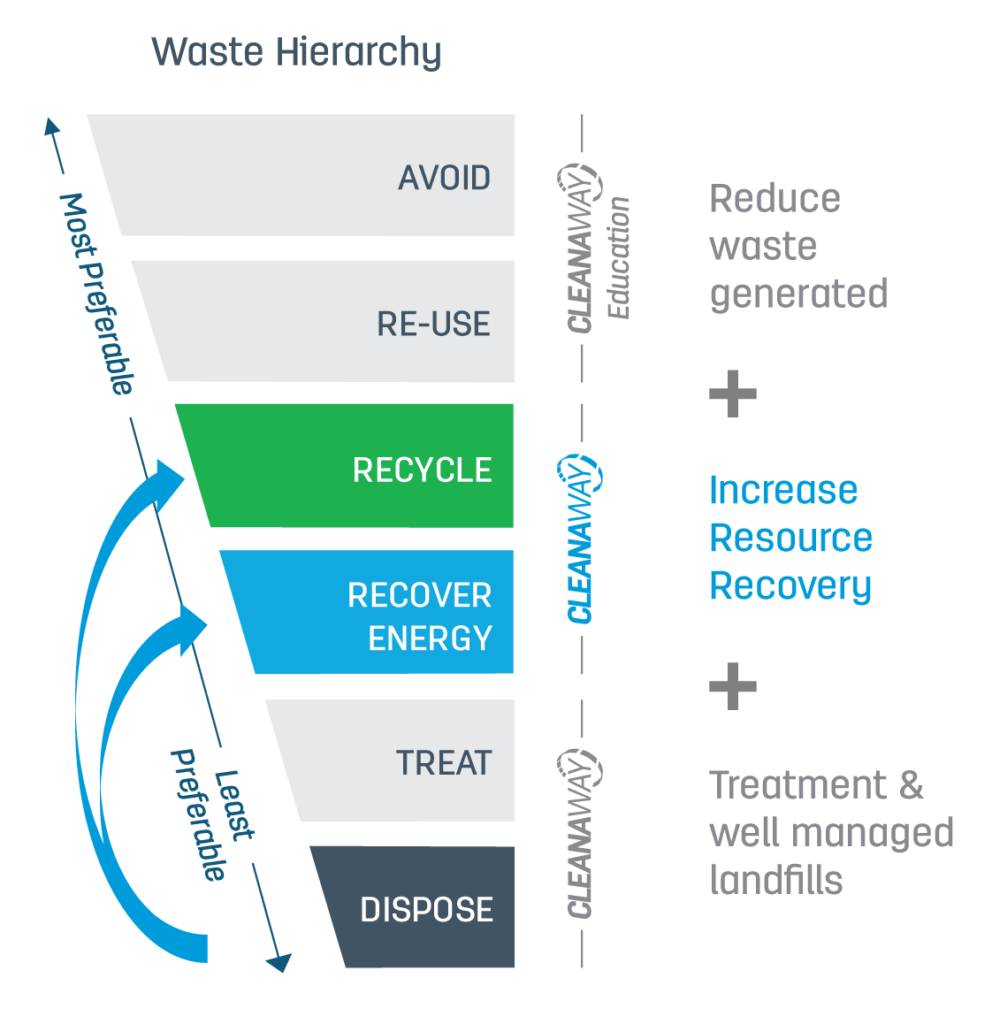

Concern: Energy-from-waste will reduce recycling rates and is contrary to a circular economy

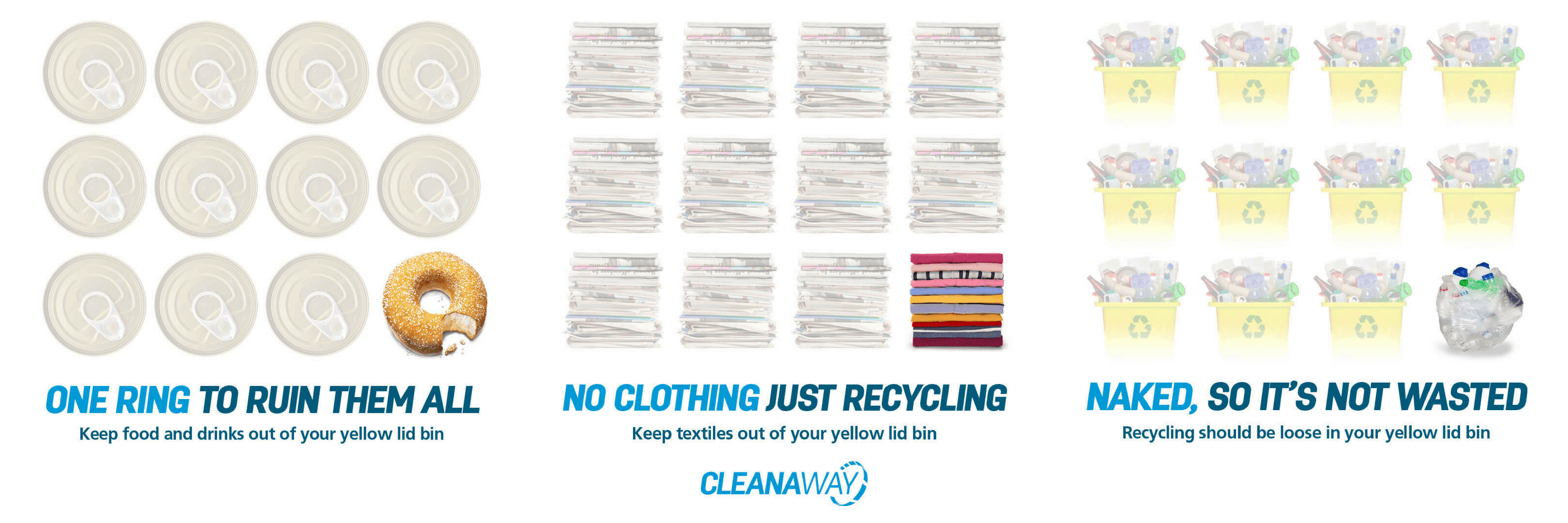

Fact: There is a misconception that because energy-from-waste facilities run 24/7, recycling will be used to ‘feed the beast’. This is inaccurate. In the case of the proposed Western Sydney Energy and Resource Recovery Centre, up to 500,000 tonnes of non-recyclable waste will be accepted. This is less than a third of the waste generated by Western Sydney alone. Even with a reduction in waste generation and improved recycling, there will still be ample non-recyclable waste that needs to be managed.

It is also not in a waste management operator’s interest to burn recyclables. Recyclable materials are valuable commodities and it does not make economic or environmental sense for them to be taken to an energy-from-waste facility. Cleanaway owns and operates recycling facilities in Sydney, including a Container Deposit Facility for NSW’s Return and Earn scheme. We have also recently entered into a partnership with Asahi and Pact Group to take recovered plastic and recycle it back into bottles – a true circular process!

Concerns that energy-from-waste will prevent progress towards a circular economy are also misguided. When implemented mindfully to complement recycling, reuse and reduction initiatives, energy-from-waste can be an incredibly effective tool for recovering resources from waste with no other recovery pathway.

Concern: Large quantities of toxic ash will need to be landfilled

Fact: Approximately 20-25% of the total mass of waste processed by the energy-from-waste facility remains after the process as ash.

This ash is made up of two components, incinerator bottom ash (IBA) and Flue Gas Treatment residues (FGTr). IBA is inert, containing combusted waste and non-combustible items such as ceramics, glass and metals. The metals are recovered and recycled (this metal would have otherwise gone to landfill). Overseas, the bottom ash is commonly repurposed into construction products, often used for road base and other non-structural uses.

The FGTr is a combination of fly ash and the air pollution control consumables and does require landfilling due to its hazardous properties. Fly ash is essentially the solidified emissions captured in the Flue Gas Treatment system and will need to be treated before being landfilled. However, the FGTr is only around 2-5% of the original mass.

This means that many modern energy-from-waste facilities are able to divert ~95% of non-recyclable waste that enters their facilities away from landfill.

Visit energyandresourcecentre.com.au to learn more about the WSERRC proposal or contact us at 1800 97 37 72 to get involved.

Read also:

Energy-from-waste: a piece of the waste management puzzle